Photos from the day when US government nuked Mississippi, 1964

Mississippi's Tatum Salt Dome near Hattiesburg in rural Lamar County was the site of two nuclear test explosions in the mid-1960s.

The salmon test on October 22, 1964, and the Stirling test on December 3, 1966, were conducted to help determine whether and how nuclear test yields could be hidden through "decoupling" and thus How well can explosions be detected?

After nine years of negotiations, the United States, the Soviet Union, and other countries signed the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) in 1963, which prohibited "any nuclear weapon test detonation, or any other nuclear explosion" in the atmosphere. done; beyond its borders, including outer space; or under water, including the water or the high seas".

The treaty did not address underground testing, due to disagreement and uncertainty about how to verify that nations were not testing underground weapons.

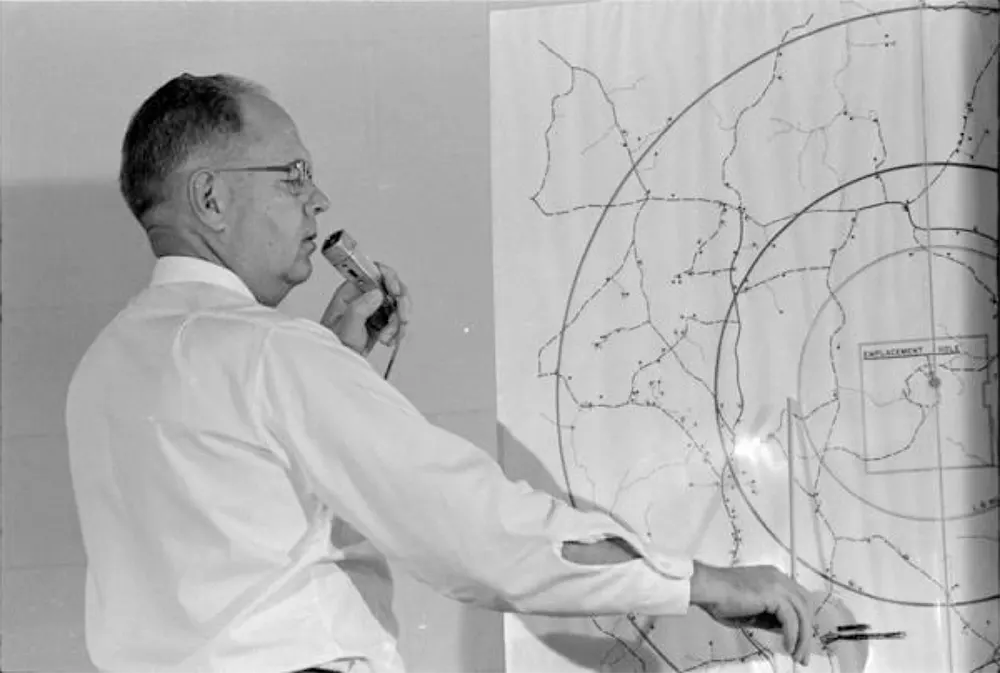

In most cases, seismographs can detect underground nuclear tests. The United States wanted to know more about underground testing and how it could be detected and designed Project Dribble, which involved two Mississippi explosions, to investigate the possibility that the betrayed nation would somehow You can hide your underground trials from

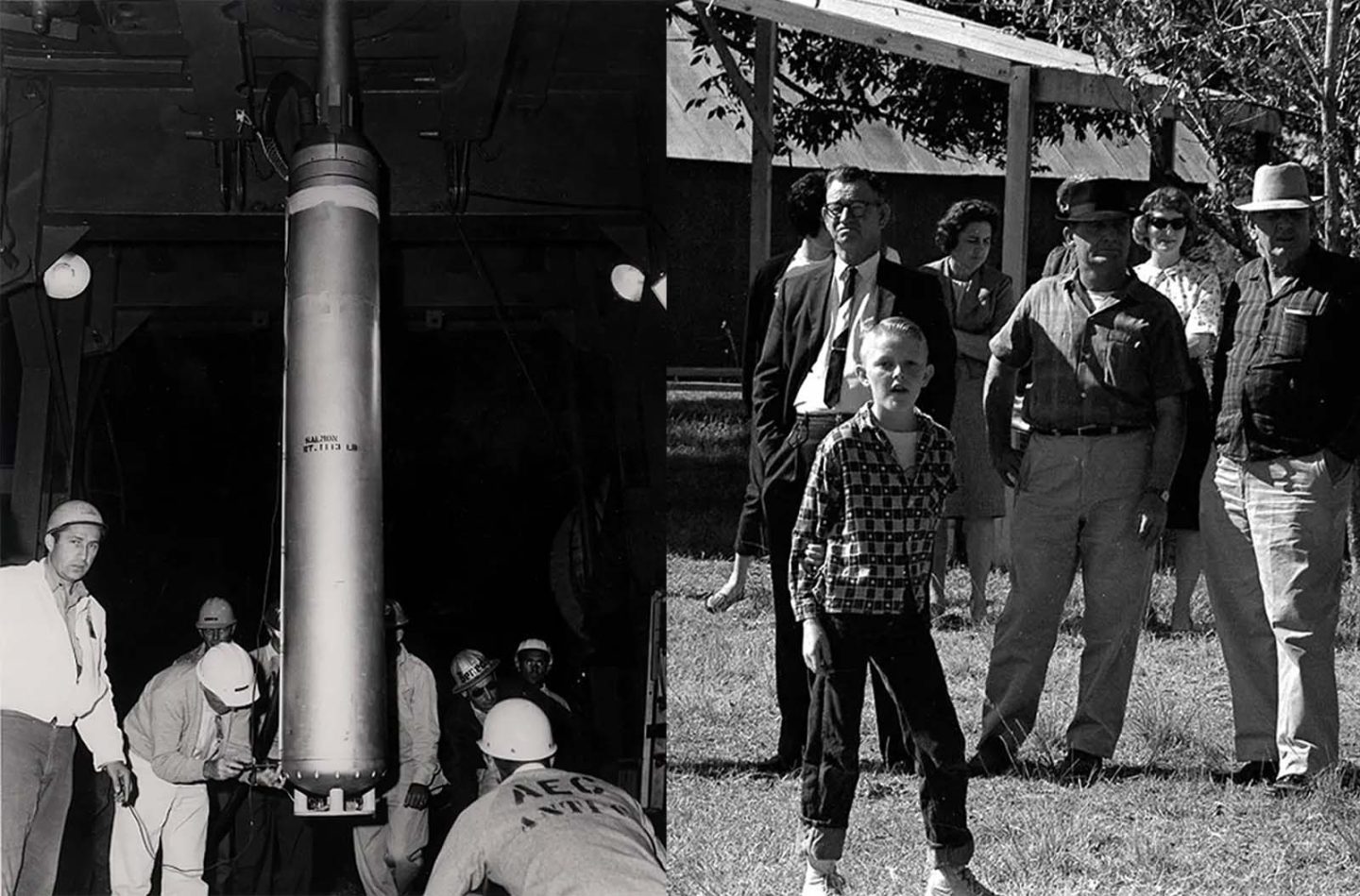

The plan called for two explosions. The first, code-named Project Salmon, would be an eruption 2,700 feet down in solid salt.

The second explosion, Project Stirling, would use a small bomb in the cavity left by the first explosion. The scientists hypothesized that the shockwaves of the second explosion would be suppressed by the cavity, effectively hiding it from seismic detection.

So in 1964, Atomic Energy Commission officials came to Mississippi and began preparing the Tatum Salt Dome site for Project Salmon.

One hundred residents of Lamar County found work on site, mainly driving trucks and heavy equipment, or providing food for project workers.

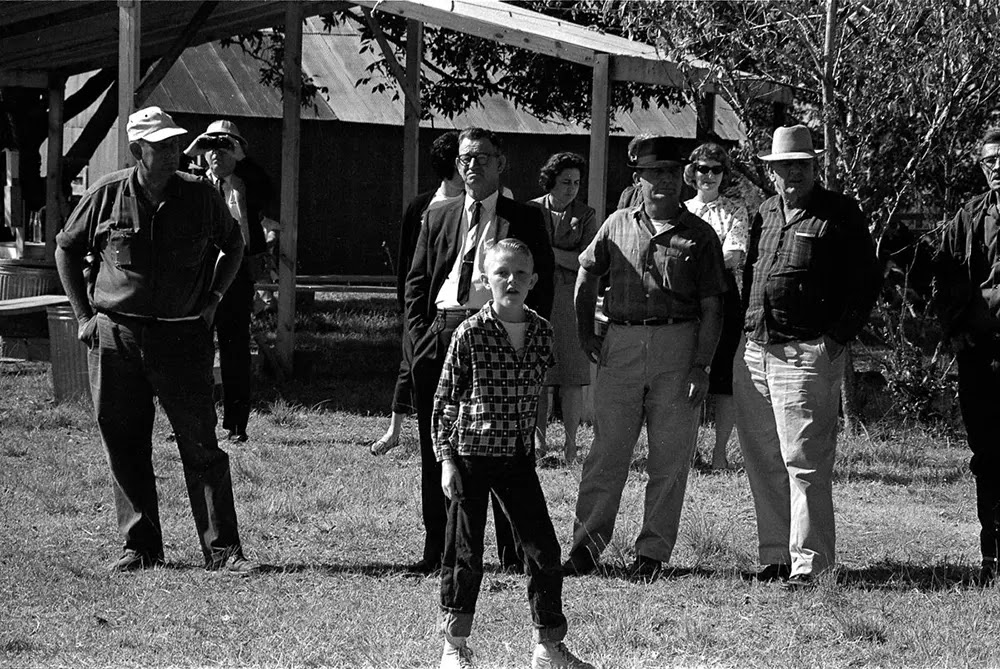

Nuclear tests were scheduled for September 22, 1964, but the wind direction was not correct until October 22. On that date, about 400 residents were evicted from the area and paid $10 per adult and $5 per child for their inconvenience.

Most residents later reported that the aftershock of the explosion was stronger than they believed. The editor of Hattiesburg American, although about thirty miles away, reported that he felt the newspaper building last for about three minutes.

At the test site, the creek turned black with silt-filled water, and seven days after the explosion, more than 400 nearby residents filed damages claims with the government, reporting that their homes had been damaged or Their water wells had dried up. ,

Horace Burge lived about two miles from the site of the explosion and returned to his three-room home to find the damage caused by the explosion.

The chimney and chimney were badly damaged, and bricks littered his living room. There were broken pots and jars on her kitchen floor, and shelves collapsed inside her refrigerator and several broken glass containers.

His electric stove was covered with ash and pieces of concrete. The pipe under his kitchen sink had burst, flooding the house with water.

Within days, the United States government began to reimburse local residents for damage to their homes.

After seismic analysis, government scientists reported that Project Salmon was successful, with the bomb producing a force similar to 5,000 tons of TNT.

The Project Salmon explosion was about a third as powerful as the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima in 1945. The bomb detonated a void in the salt, which was, as predicted, a circular cavity about 110 feet in diameter.

The Project Stirling explosion on December 3, 1966, was much weaker than the eruption two years earlier, as it was intended.

Instead of the 5,000 tons of TNT developed by Project Salmon, Project Stirling's bomb had a force of 350 tons of TNT.

Observers two miles from the explosion reported that they barely felt a collision. Like Project Salmon, Project Sterling was labeled a success.

US government officials reported that the two Mississippi nuclear explosions as part of Project Dribble helped to prove that the seismic effects of a nuclear detonation could in fact be greatly reduced if such a detonation were to occur in a large enough area. installed in a cave.

It suggested that it might be possible for a nation to cheat on a future nuclear test ban by concealing a nuclear test. It also helped teach nuclear scientists how to detect and measure such hidden explosions.

In the early 1990s, residents of Hattiesburg and workers at Projects Dribble and Stirling began to fear that radiation from these projects caused cancer-related deaths.

In 2015, the federal government paid a total of $16.8 million to former workers and contractors who worked on these projects and "workers living in Mississippi but not required to work" on these projects.

A granite monument surrounded by test wells, in a clearing surrounded by the Mississippi State Wood Preserve, marks the site of the atomic bomb tests.

No comments: